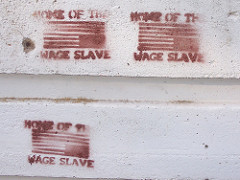

The manager spoke passionately about healthcare reform. The day’s presentation had been a crash course in toned-down Patch Adams style relationships; ways for workers to interact more personally with their patients – though not at the expense of threatening the existent managerial hierarchy. He wrapped up with this statement: “We all know why we’re in healthcare. We’re here, not because of the money, but because of the patients.”

The manager spoke passionately about healthcare reform. The day’s presentation had been a crash course in toned-down Patch Adams style relationships; ways for workers to interact more personally with their patients – though not at the expense of threatening the existent managerial hierarchy. He wrapped up with this statement: “We all know why we’re in healthcare. We’re here, not because of the money, but because of the patients.”

Although there were murmurs and nods of agreement, I did not see anyone move to hand back their paycheck.

This highlights the supposed motivational quandry between capitalism and socialism. Capitalism has ridiculously uneven financial rewards, leaving many with barely enough to scrape by. Socialism poses the problem of motivation: Why go through extra effort, training, and drudgery without financial reward? Yet financial rewards alone – as evidenced by the statements of the manager – are not seen as a pure or good motivation in and of itself.

This dilemma is a false one. It is created by a misunderstanding and an overgeneralization. The first is a misunderstanding or imperfect appreciation of Marx’s term alienation. What is frequently comprehended is when alienation exists, and its consequences. We can intuitively empathize with an alienated worker. The sensibility of being unfulfilled by one’s work is a common experience in our industrial society. Consider the terms “rat race”, or the expressions in popular media through television shows like “The Office”, or the movies Office Space, American Beauty, or even The Incredibles. The opposite, however, has rarely been seen as a natural part of work. Instead, fulfillment and meaning was sought throughout the 20th Century through hobbies, social groups and sports, or volunteer work. It was only with the economic boom of the late 1990’s that statements like “follow your bliss” became legitimate advice instead of countercultural polemic. That sensibility and advice has continued through a recession and a half; the expectation has shifted towards both workers and managers expecting work to be fulfilling and meaningful for all involved. That ideal – doing work that you love and find fulfilling – is the opposite of alienation.

It is also payment.

Neoclassical economists and functionalists alike concentrate on monetary wages, forgetting that payment can be things other than wages. I do not mean “fringe benefits” such as healthcare coverage, onsite daycare, ego stroking, or casual Fridays – though the last two come closer than the others. For some, a stressful and demanding job in an emergency room is intrinsically exciting and rewarding. For others, it would be a nightmare, who would prefer a more aloof healthcare job taking x-rays or doing hour-long scans. The vast majority of jobs are not differentiated by required intrinsic skill; instead, they are differentiated by training. Most people, provided adequate training, could be capable of doing nearly all jobs. But a job fulfilling to one person may not be “worth it” to another.

We implicitly acknowledge this reality in our everyday lives. Some choose the reward of living in the country to work. Some find it rewarding to live in the city. A person may choose to teach, even if the private sector could provide a bigger paycheck. Another may choose to be a professor at a less-competitive school to avoid the competitive stress, regardless of their own aptitude. On a recent episode of the podcast Planet Money, an economist interviewed a blue collar worker who had excellent job security and satisfaction simply because he could leave his work at work.

In Scott Adams’ daily cartoon Dilbert, the smartest man in the world is also Dilbert’s garbage collector. As Adams points out: If the smartest man in the world wants to be a garbage collector, who are we to argue with him?